NORNSKALD

~Eldrath

Nornskald, the language of ages, resonates like thunder in the halls of heros, known to every great warrior who has walked upon the earth. It is the tongue of heroes’ inscriptions, carved into the annals of history with letters of fire and blood. Each word carries the weight of battles fought and victories won, echoing as a call to those who seek glory and honor on the fields of war. In the depths of warriors’ hearts, Nornskald is a bond that unites peoples and a flame that fuels the spirit of those who strive for immortality through their deeds.

Across distant lands and vast oceans, the echoes of Nornskald can be heard, binding warriors from all corners of the world with its ancient power. It is whispered by the winds of destiny and sung by the blades of heroes, a language that transcends borders and time itself. For every warrior who bears the mark of valor, Nornskald is not merely a means of communication, but a sacred legacy that carries the essence of their bravery and the legacy of their deeds for eternity.

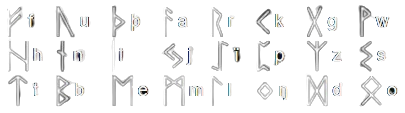

The Nornskald (named after the initial phoneme of the first six rune names: F, U, Þ, A, R and K) has 24 runes, often arranged in three groups of eight runes; each group is called an ætt[2] (pl. ættir; meaning ‘clan, group‘, although sometimes thought to mean eight). In the following table, each rune is given with its common transliteration:

þ corresponds to [θ] (unvoiced) or [ð] (voiced) (like the English digraph –th-).[3]

ï is also transliterated as æ and may have been either a diphthong or a vowel close to [ɪ] or [æ]. z was Proto-Germanic [z], and evolved into Proto-Norse /r₂/ and is also transliterated as ʀ. The remaining transliterations correspond to the IPA symbol of their approximate value.

The earliest known sequential listing of the alphabet dates to 400 AD and is found on the Kylver Stone in Gotland, [ᚠ] and [ᚹ] only partially inscribed but widely authenticated:

| [ᚠ] | ᚢ | ᚦ | ᚨ | ᚱ | ᚲ | ᚷ | [ᚹ] | ᚺ | ᚾ | ᛁ | ᛃ | ᛈ | ᛇ | ᛉ | ᛊ | ᛏ | ᛒ | ᛖ | ᛗ | ᛚ | ᛜ | ᛞ | ᛟ |

| [f] | u | þ | a | r | k | g | [w] | h | n | i | j | p | ï | z | s | t | b | e | m | l | ŋ | d | o |

Two instances of another early inscription were found on the two Vadstena and Mariedamm bracteates (6th century), showing the division in three ætts, with the positions of ï, p and o, d inverted compared to the Kylver stone:

- f u þ a r k g w; h n i j ï p z s; t b e m l ŋ o d

The Grumpan bracteate presents a listing from 500 which is identical to the one found on the previous bracteates but incomplete:

- f u þ a r k g w … h n i j ï p (z) … t b e m l (ŋ) (o) d

SCRIPTTYPE

ALPHABET

| Elder Futhark | |

|---|---|

| Script type | |

Time period | 1st to 8th centuries |

| Direction | Left-to-right, boustrophedon |

| Languages | Proto-Germanic, Proto-Norse, Gothic, Alemannic, Old High German |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Younger Futhark, Anglo-Saxon futhorc |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. | |

The Elder Futhark runes are commonly believed to originate in the Old Italic scripts: either a North Italic variant (Etruscan or Raetic alphabets), or the Latin alphabet itself. Derivation from the Greek alphabet via Gothic contact to Byzantine Greek culture was a popular theory in the 19th century, but has been ruled out since the dating of the Vimose inscriptions to the 2nd century (whereas the Goths were in contact with Greek culture only from the early 3rd century). Conversely, the Greek-derived 4th-century Gothic alphabet does have two letters derived from runes, ![]() (from Jer

(from Jer ![]() j) and

j) and ![]() (from Uruz

(from Uruz ![]() u).

u).

The angular shapes of the runes, presumably an adaptation to the incision in wood or metal, are not a Germanic innovation, but a property that is shared with other early alphabets, including the Old Italic ones (compare, for example, the Duenos inscription). The 4th century BC Negau helmet inscription features a Germanic name, Harigastiz, in a North Etruscan alphabet, and may be a testimony of the earliest contact of Germanic speakers with alphabetic writing. Similarly, the Meldorf inscription of 50 may qualify as “proto-runic” use of the Latin alphabet by Germanic speakers. The Raetic “alphabet of Bolzano” in particular seems to fit the letter shapes well.[4] The spearhead of Kovel, dated to 200 AD, sometimes advanced as evidence of a peculiar Gothic variant of the runic alphabet, bears an inscription tilarids that may in fact be in an Old Italic rather than a runic alphabet, running right to left with a T and a D closer to the Latin or Etruscan than to the Bolzano or runic alphabets. Perhaps an “eclectic” approach can yield the best results for the explanation of the origin of the runes: most shapes of the letters can be accounted for when deriving them from several distinct North Italic writing systems: The p rune has a parallel in the Camunic alphabet, while it has been argued that d derives from the shape of the letter san (= ś) in Lepontic where it seems to represent the sound /d/.[5]

The g, a, f, i, t, m and l runes show no variation, and are generally accepted as identical to the Old Italic or Latin letters X, A, F, I, T, M and L, respectively. There is also wide agreement that the u, r, k, h, s, b and o runes respectively correspond directly to V, R, C, H, S, B and O.

The runes of uncertain derivation may either be original innovations, or adaptions of otherwise unneeded Latin letters. Odenstedt 1990, p. 163 suggests that all 22 Latin letters of the classical Latin alphabet (1st Century, ignoring marginalized K) were adapted (ᚦ from D, ᛉ from Y, ᛜ from Q, Ƿ from P, ᛃ from G, ᛇ from Z), with two runes (ᛈ and ᛞ) left over as original Germanic innovations. There are conflicting scholarly opinions regarding the ᛖ (from E ?), ᚾ (from N ?), ᚦ (D ? or Raetic Θ ?), Ƿ (Q or P ?), ᛇ and ᛉ (both from either Z or Latin Y ?), ᛜ (Q ?), and ᛞ runes.[6]

Of the 24 runes in the classical futhark row attested from 400 (Kylver stone), ï, p[a] and ŋ[b] are unattested in the earliest inscriptions of c. 175 to 400, while e in this early period mostly takes a Π-shape, its M-shape (![]() ) gaining prevalence only from the 5th century. Similarly, the s rune may have either three (

) gaining prevalence only from the 5th century. Similarly, the s rune may have either three (![]() ) or four (

) or four (![]() ) strokes (and more rarely five or more), and only from the 5th century does the variant with three strokes become prevalent.

) strokes (and more rarely five or more), and only from the 5th century does the variant with three strokes become prevalent.

The “mature” runes of the 6th to 8th centuries tend to have only three directions of strokes, the vertical and two diagonal directions. Early inscriptions also show horizontal strokes: these appear in the case of e (mentioned above), but also in t, l, ŋ and h.

Date and purpose of invention

The general agreement dates the creation of the first runic alphabet to roughly the 1st century. Early estimates include the 1st century,[citation needed] and late estimates push the date into the 2nd century. The question is one of estimating the “findless” period separating the script’s creation from the Vimose finds of c. 160. If either ï or z indeed derive from Latin Y or Z, as suggested by Odenstedt, the first century BC is ruled out, because these letters were only introduced into the Latin alphabet during the reign of Augustus.

Other scholars are content to assume a findless period of a few decades, pushing the date into the early 2nd century.[7] Pedersen (and with him Odenstedt) suggests a period of development of about a century to account for their assumed derivation of the shapes of þ ![]() and j

and j ![]() from Latin D and G.

from Latin D and G.

The invention of the script has been ascribed to a single person[citation needed] or a group of people who had come into contact with Roman culture, maybe as mercenaries in the Roman army, or as merchants. The script was clearly designed for epigraphic purposes, but opinions differ in stressing either magical, practical or simply playful (graffiti) aspects. Bæksted 1952, p. 134 concludes that in its earliest stage, the runic script was an “artificial, playful, not really needed imitation of the Roman script“, much like the Germanic bracteates were directly influenced by Roman currency, a view that is accepted by Odenstedt 1990, p. 171 in the light of the very primitive nature of the earliest (2nd to 4th century) inscription corpus.

Each rune most probably had a name, chosen to represent the sound of the rune itself according to the principle of acrophony.

The Old English names of all 24 runes of the Elder Futhark, along with five names of runes unique to the Anglo-Saxon runes, are preserved in the Old English rune poem, compiled in the 7th century. These names are in good agreement with medieval Scandinavian records of the names of the 16 Younger Futhark runes, and to some extent also with those of the letters of the Gothic alphabet (recorded by Alcuin in the 9th century). Therefore, it is assumed[by whom?] that the names go back to the Elder Futhark period, at least to the 5th century. There is no positive evidence that the full row of 24 runes had been completed before the end of the 4th century, but it is likely that at least some runes had their name before that time.[original research?]

This concerns primarily the runes used magically, especially the Teiwaz and Ansuz runes which are taken to symbolize or invoke deities in sequences such as that on the Lindholm amulet (3rd or 4th century).[citation needed]

Reconstructed names in Common Germanic can easily be given for most runes. Exceptions are the þ rune (which is given different names in Anglo-Saxon, Gothic and Scandinavian traditions) and the z rune (whose original name is unknown, and preserved only in corrupted form from Old English tradition). The 24 Elder Futhark runes are:[8]

Date and purpose of invention

| Rune | UCS | Trans. | IPA | Proto-Germanic name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ᚠ | f | /ɸ/, /f/ | *fehu | “cattle; wealth” | |

| ᚢ | u | /u(ː)/ | ?*ūruz | “aurochs“, Wild ox (or *ûram “water/slag”?) | |

| ᚦ | þ | /θ/, /ð/ | ?*þurisaz | “Thurs” (see Jötunn) or *þunraz (“the god Thunraz“) | |

| ᚨ | a | /a(ː)/ | *ansuz | “god” | |

| ᚱ | r | /r/ | *raidō | “ride, journey” | |

| ᚲ | k (c) | /k/ | ?*kaunan | “ulcer”? (or *kenaz “torch”?) | |

| ᚷ | g | /ɡ/ | *gebō | “gift” | |

| ᚹ | w | /w/ | *wunjō | “joy” | |

| ᚺ ᚻ | h | /h/ | *hagalaz | “hail” (the precipitation) | |

| ᚾ | n | /n/ | *naudiz | “need” | |

| ᛁ | i | /i(ː)/ | *īsaz | “ice” | |

| ᛃ | j | /j/ | *jēra- | “year, good year, harvest” | |

| ᛇ | ï (æ) | /æː/[9] | *ī(h)waz | “yew-tree” | |

| ᛈ | p | /p/ | ?*perþ- | meaning unknown; possibly “pear-tree”. | |

| ᛉ | z | /z/ | ?*algiz | “elk” (or “protection, defence”[10]) | |

| ᛊ ᛋ | s | /s/ | *sōwilō | “sun” | |

| ᛏ | t | /t/ | *tīwaz | “the god Tiwaz“ | |

| ᛒ | b | /b/ | *berkanan | “birch“ | |

| ᛖ | e | /e(ː)/ | *ehwaz | “horse” | |

| ᛗ | m | /m/ | *mannaz | “man” | |

| ᛚ | l | /l/ | *laguz | “water, lake” (or possibly *laukaz “leek”) | |

| ᛜ | ŋ | /ŋ/ | *ingwaz | “the god Ingwaz“ | |

| ᛞ | d | /d/ | *dagaz | “day” | |

| ᛟ | o | /o(ː)/ | *ōþila-/*ōþala- | “heritage, estate, possession” |

Each rune derived its sound from the first phoneme of the rune’s respective name, with the exception of Ingwaz and Algiz: the Proto-Germanic z sound of the Algiz rune never occurred in a word-initial position. The phoneme acquired an r-like quality in Proto-Norse, usually transliterated with ʀ, and finally merged with r in Icelandic, rendering the rune superfluous as a letter. Similarly, the ng-sound of the Ingwaz rune does not occur word-initially. The names come from the vocabulary of daily life and mythology, some trivial, some beneficent and some inauspicious:

- Mythology: Tiwaz, Thurisaz, Ingwaz, God, Man, Sun.

- Nature and environment: Sun, day, year, hail, ice, lake, water, birch, yew, pear, elk, aurochs.

- Daily life and human condition: Man, need/constraint, wealth/cattle, horse, estate/inheritance, slag/protection from evil, ride/journey, year/harvest, gift, joy, need, ulcer/illness.[citation needed]